Virtual Exhibit

Are you passionate about culture & heritage and Lacombe’s local history?

Learn more about how to be part of the Historical Society team, or Executive Board, discover new volunteer opportunities in your communities, or be a heritage hero and donate today!

Gratefully Supported by

ADMIN OFFICE

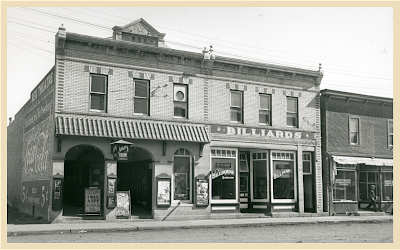

Flatiron Building Museum

Suite #200, 5005 50th Ave, Lacombe AB T4L2L1

(403) 782-3933

SUMMER HOURS

Victoria Day – Labour Day Long Weekend

Flatiron Building Museum

OPEN Wed-Sun 10 am – 4 pm

Blacksmith Shop Museum

OPEN Wed-Sun 10 am – 4 pm

Michener House Museum

OPEN Wed-Sun 10 am – 4 pm

The Lacombe & District Historical Society acknowledges that we are working, volunteering, and living on Treaty 6 Territory and the Métis homeland, a traditional gathering place for diverse Indigenous Peoples including the Maskwacis Nēhiyaw (Bear Hills Cree), Niitsítapi (Blackfoot), Nakoda (Stony), Dene (Athabascan), Métis and many other distinct Indigenous Peoples whose footsteps have walked these lands for time immemorial, and whose history, culture, and language continues to influence our vibrant community.

To learn more, please visit our Treaty No. 6 resource page.

The Lacombe & District Historical Society is a registered Alberta Society’s Act Non-profit Organization & CRA Recognized Charity

Charity No: 119244416RR0001

©2023 Lacombe Museum

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!